1 CEFR principles of good practice

Using the CEFR:

Principles of Good Practice

October 2011

‘What [the CEFR] can do is to stand as a central point of reference, itself always open to amendment and further development, in an interactive international system of co-operating institutions … whose cumulative experience and expertise produces a solid structure of knowledge, understanding and practice shared by all.’

‘What [the CEFR] can do is to stand as a central point of reference, itself always open to amendment and further development, in an interactive international system of co-operating institutions … whose cumulative experience and expertise produces a solid structure of knowledge, understanding and practice shared by all.’

John Trim (Green in press 2011:xi)

A brief history of the CEFR 5

| Contents

Introduction 2 Section 1: Overview 3 What the CEFR is … and what it is not 4 |

|

1

How to read the CEFR 7

The action-oriented approach 7

The common reference levels 8

Language use and the learner’s competences 9

Section 2: Principles and general usage 11

Principles for teaching and learning 12

Using the CEFR in curriculum and syllabus design 12

Using the CEFR in the classroom: teaching and lesson planning 13

Principles for assessment 16

Using the CEFR to choose or commission appropriate assessments 16

Using the CEFR in the development of assessments 17

Principles for development and use of Reference Level Descriptions 21

Using resources from Reference Level Descriptions in learning,

teaching and assessment 21

Using the CEFR to develop Reference Level Descriptions 23

Section 3: Applying the CEFR in practice 25

Applying the CEFR in practice: Aligning Cambridge ESOL examinations

to the CEFR 26

Point 1 – Shared origins and long-term engagement 28

Point 2 – Integrated item banking and calibration systems 29

Point 3 – Quality management and validation systems 29

Point 4 – Alignment and standard-setting studies 30

Point 5 – Application and extension of the CEFR for English 31

Summary 31

Appendices 33

Appendix A – Reference Level Descriptions 34

Appendix B – References 36

Using the CEFR: Principles of Good Practice

2

Introduction

The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment (CEFR) was created by the Council

of Europe to provide ‘a common basis for the elaboration of language syllabuses, curriculum guidelines, examinations, textbooks, etc. across Europe’ (2001a:1). It was envisaged primarily as a planning tool whose aim was to promote ‘transparency and coherence’ in language education.

The CEFR is often used by policy-makers to set minimum language requirements for a wide range of purposes. It is also widely used in curriculum planning, preparing textbooks and many other contexts. It can be a valuable tool for all of these purposes, but users need to understand its limitations and original intentions. It was intended to be a ‘work in progress’, not an international standard or seal of approval. It should be seen as a general guide rather than a prescriptive instrument and does not provide simple, ready-made answers or a single method for applying it. As the authors state in the ‘Notes for the User’:

We have NOT set out to tell practitioners what to do or how to do it. We are raising questions not answering them. It is not the function of the CEF(R) to lay down the objectives that users should pursue or the methods they should employ.

(2001a:xi)

The CEFR is useful to you if you are involved in learning, teaching or assessing languages. We have aimed this booklet at language professionals such as teachers and administrators rather than candidates or language learners. It is based on Cambridge ESOL’s extensive experience of working with the CEFR over many years.

The CEFR is a comprehensive document, and as such, individual users can find it difficult to read and interpret. The Council of Europe has created a number of guidance documents to help in this interpretation. Helping you find your way around the CEFR and its supporting documents is one of our key aims in creating Using the CEFR: Principles of Good Practice. If you want a brief overview of the CEFR read Section 1 of this booklet. If you are a teacher or administrator working in an educational setting and would like guidance on using and interacting with the CEFR then reading Section 2 will be useful to you. If you want to find out about how Cambridge ESOL works with the CEFR then read Section 3. Each section is preceded by a page that signposts key further reading.

Section 1: Overview

Council of Europe (2001a) Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. In particular ‘Notes for the User’ and Chapters 3, 4 and 5.

KEY RESOURCES

‘The Framework aims to be not only comprehensive, transparent and coherent, but also open, dynamic and non-dogmatic.’

Council of Europe (2001a:18)

Using the CEFR: Principles of Good Practice

4

What the CEFR is … and what it is not

The CEFR is a framework, published by the Council of Europe in 2001, which describes language learners’ ability in terms of

speaking, reading, listening and writing at six reference levels.

These six levels are named as follows:

C2 Mastery } Proficient user

C1 Effective Operational Proficiency

B2 Vantage } Independent user

B1 Threshold

A2 Waystage } Basic user

A1 Breakthrough

As well as these common reference levels, the CEFR provides a Descriptive Scheme’ (2001a:21) of definitions, categories and examples that language professionals can use to better understand and communicate their aims and objectives. The examples given are called illustrative descriptors’ and these are presented as a series of scales with Can Do statements from levels A1 to C2. These scales can be used as a tool for comparing levels of ability amongst learners of foreign languages and also offer a means to map the progress’ of learners (2001a:xii).

The scales in the CEFR are not exhaustive. They cannot cover every possible context of language use and do not attempt to do so. Whilst they have been empirically validated, some of them still have significant gaps, e.g. at the lowest level (A1) and at the top of the scale (the C levels). Certain contexts are less well elaborated, e.g. young learners.

The CEFR is not an international standard or seal of approval. Most test providers, textbook writers and curriculum designers now claim links to the CEFR. However, the quality of the claims can vary (as can the quality of the tests, textbooks and curricula themselves). There is no single best’ method of carrying out an alignment study or accounting for claims which are made. What is required is a reasoned explanation backed up by supporting evidence.

The CEFR is not language or context specific. It does not attempt to list specific language features (grammatical rules, vocabulary, etc.) and cannot be used as a curriculum or checklist of learning points. Users need to adapt its use to fit the language they are working with and their specific context.

One of the most important ways of adapting the CEFR is the production of language-specific Reference Level Descriptions. These are frameworks for specific languages where the levels and descriptors in the CEFR have been mapped against the actual linguistic material (i.e. grammar, words) needed to implement the stated competences. Reference Level Descriptions are already available for several languages (see Appendix A).

Section 1: Overview

5

A brief history of the CEFR

The CEFR is the result of developments in language education that date back to the 1970s and beyond, and its publication in 2001 was the direct outcome of several discussions, meetings and consultation processes which had taken place over the previous 10 years.

The development of the CEFR coincided with fundamental changes in language teaching, with the move away from the grammar-translation method to the functional/notional approach and the communicative approach. The CEFR reflects these later approaches.

The CEFR is also the result of a need for a common international framework for language learning which would facilitate co-operation among educational institutions in different countries, particularly within Europe. It was also hoped that it would provide a sound basis for the mutual recognition of language qualifications and help learners, teachers, course designers, examining bodies and educational administrators to situate their own efforts within a wider frame of reference.

The years since the publication of the CEFR have seen the emergence of several CEFR-related projects and the development of a ‘toolkit’ for working with the CEFR. The concept of developing Reference Level Descriptions for national and regional languages has also been widely adopted. These developments and their associated outcomes will continue into the future, adding to the evolution of the Framework. In this way the CEFR is able to remain relevant and accommodate new innovations in teaching and learning.

Also see Figure 1 on p.6 for a summary of the development of the CEFR.

|

– to establish a useful tool for communication that will enable practitioners in many diverse contexts to talk about objectives and language levels in a more coherent way – to encourage practitioners to reflect on their current practice in the setting of objectives and in tracking the progress of learners with a view to improving language teaching and assessment across the continent.

|

|

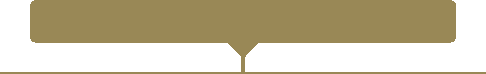

Figure 1. Summary of the development of the CEFR

Figure 1. Summary of the development of the CEFR

- The Council of Europe’s Modern Languages projects start in the 1960s and (following the 1971 intergovernmental symposium in Rüschlikon) include a European unit/credit scheme for adult education. It is in the context of this project that the concept of a ‘threshold’ level first arises (Bung 1973).

- Publication of the Threshold level (now Level B1 of the CEFR) (van Ek 1975) and the Waystage level (van Ek, Alexander and Fitzpatrick 1977) (now Level A2 of the CEFR).

- Publication of Un niveau-seuil (Coste, Courtillon, Ferenczi, Martins-Baltar and Papo 1976), the French version of the Threshold model.

- 1977 Ludwigshafen Symposium: David Wilkins speaks of a possible set of seven ‘Council of Europe Levels’ (North 2006:8) to be used as part of the European unit/credit scheme.

Using the CEFR: Principles of Good Practice

1960s and 1970s

Emerge nce of the functional/

notional approach

1980s

1990s

2000s

The communicative

approach

6

The development of the Framework and a

period of convergence

Using the Framework and the

em ergence of the ‘toolkit’

CEFR is about ‘raising questions, not answering them’ (2001a:xi), and one of the key aims of the CEFR book is stated as being to encourage the reader to reflect on these questions and provide answers which are relevant for their contexts and their learners.

CEFR is about ‘raising questions, not answering them’ (2001a:xi), and one of the key aims of the CEFR book is stated as being to encourage the reader to reflect on these questions and provide answers which are relevant for their contexts and their learners.

Section 1: Overview

How to read the CEFR

Throughout the CEFR book the emphasis is on the readers and their own contexts. The language practitioner is told that the

7

The CEFR has nine chapters, plus a useful introductory section called ‘Notes for the User’. The key chapters for most readers will be Chapters 2 to 5. Chapter 2 explains the approach the CEFR adopts and lays out a descriptive scheme that is then followed in Chapters 4 and 5 to give a more detailed explanation of these parameters. Chapter 3 introduces the common reference levels.

Chapters 6 to 9 of the CEFR focus on various aspects of learning, teaching and assessment; for example, Chapter 7 is about ‘Tasks and their role in language teaching’. Each chapter explains concepts to the reader and gives a structure around which to ask and answer questions relevant to the reader’s contexts. The CEFR states that the aim is ‘not to prescribe or even recommend a particular method, but to present options’ (2001a:xiv).

The action-oriented approach

Chapter 2 of the CEFR describes a model of language use which is referred to as the ‘action-oriented approach’, summarised in the following paragraph (2001a:9):

Language use, embracing language learning, comprises the actions performed by persons who as individuals and as social agents develop a range of competences, both general and in particular communicative language competences. They draw on the competences at their disposal in various contexts under various conditions and under various constraints to engage in language activities involving language processes to produce and/or receive texts in relation to themes in specific domains, activating those strategies which seem most appropriate for carrying out the tasks to be accomplished. The monitoring of these actions by the participants leads to the reinforcement or modification of their competences.

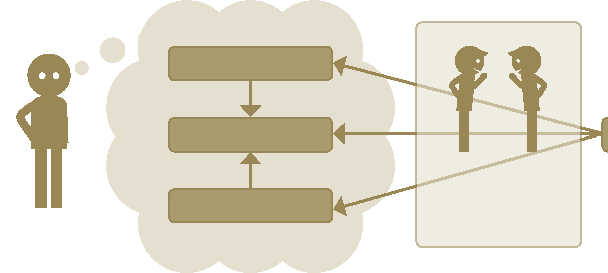

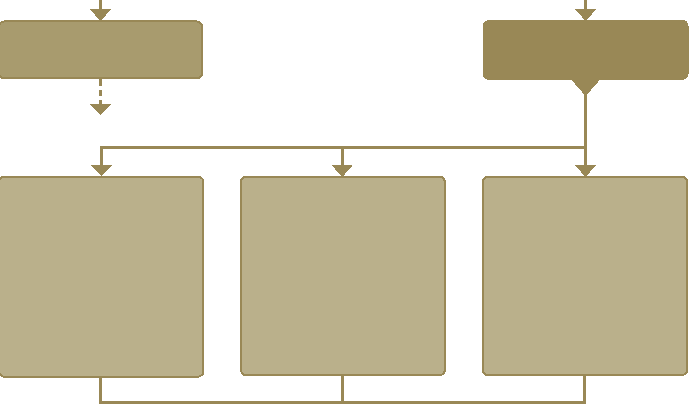

This identifies the major elements of the model, which are then presented in more detail in the text of the CEFR. It also sets out a socio-cognitive approach (see Weir 2005 for more detail), highlighting the cognitive processes involved in language learning and use, as well as the role of social context in how language is learned and used. The model is illustrated in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. A representation of the CEFR’s model of language use and learning

The language learner/user

Knowledge

Strategies

Processes

Language activity

|

|

| Task | |

Domain of use

Using the CEFR: Principles of Good Practice

The diagram shows a language user, whose developing competence reflects various kinds of cognitive processes, strategies and knowledge. Depending on the contexts in which the learner needs to use the language, he/she is faced with tasks to perform. The user engages in language activities to complete the tasks. These engage his/her cognitive processes, which also leads to learning.

The diagram highlights the centrality of language activity in this model. Language activity is the observable performance on a speaking, writing, reading or listening task (a real-world task, or a classroom task). Observing this activity allows teachers to give useful formative feedback to their students, which in turn leads to learning.

The common reference levels

Like other frameworks, the CEFR covers two main dimensions: a vertical and a horizontal one. The vertical dimension of the CEFR shows progression through the levels. This is presented in the form of the set of common reference levels (discussed in Chapter 3 of the CEFR) and shown in Figure 3 below.

8

| Proficient User | C2 | Can understand with ease virtually everything heard or read. Can summarise information from different spoken and written sources, reconstructing arguments and accounts in a coherent presentation. Can express him/herself spontaneously, very fluently and precisely, differentiating finer shades of meaning even in more complex situations. | ||

| C1 | Can understand a wide range of demanding, longer texts, and recognise implicit meaning. Can express him/ herself fluently and spontaneously without much obvious searching for expressions. Can use language flexibly and effectively for social, academic and professional purposes. Can produce clear, well-structured, detailed text on complex subjects, showing controlled use of organisational patterns, connectors and cohesive devices. | |||

| Independent User | B2 | Can understand the main ideas of complex text on both concrete and abstract topics, including technical discussions in his/her field of specialisation. Can interact with a degree of fluency and spontaneity that makes regular interaction with native speakers quite possible without strain for either party. Can produce clear, detailed text on a wide range of subjects and explain a viewpoint on a topical issue giving the advantages and disadvantages of various options. | ||

| B1 | Can understand the main points of clear standard input on familiar matters regularly encountered in work, school, leisure, etc. Can deal with most situations likely to arise whilst travelling in an area where the language is spoken. Can produce simple connected text on topics which are familiar or of personal interest. Can describe experiences and events, dreams, hopes & ambitions and briefly give reasons and explanations for opinions and plans. |

| Basic User | A2 | Can understand sentences and frequently used expressions related to areas of most immediate relevance (e.g. very basic personal and family information, shopping, local geography, employment). Can communicate in simple and routine tasks requiring a simple and direct exchange of information on familiar and routine matters. Can describe in simple terms aspects of his/her background, immediate environment and matters in areas of immediate need. | ||

| A1 | Can understand and use familiar everyday expressions and very basic phrases aimed at the satisfaction of needs of a concrete type. Can introduce him/herself and others and can ask and answer questions about personal details such as where he/she lives, people he/she knows and things he/she has. Can interact in a simple way provided the other person talks slowly and clearly and is prepared to help. |

Figure 3. Table 1: Common Reference Levels:global scale from Chapter 3 of the CEFR (2001a:24)

Section 1: Overview

9

The language skills (reading, writing, listening, spoken interaction and spoken production) are dealt with in Tables 2 and 3 of the CEFR. Table 2 (2001a: 26–27) differentiates language activities for the purpose of self-evaluation. It therefore recasts the traditional Can Do statements into I Can Do statements appropriate for self-evaluation in pedagogic contexts; for example, in the case of Reading a low-level (A1) statement is:

I can understand familiar names, words and very simple sentences, for example on notices and posters or in catalogues.

whereas a high-level (C2) statement is:

I can read with ease virtually all forms of the written language, including

abstract,structurally or linguistically complex texts such as manuals, specialised articles and literary works.

Table 3 of the CEFR (2001a:28–29) then differentiates the levels with respect to qualitative aspects of spoken language use (range, accuracy, fluency, interaction and coherence).

Language use and the learner’s competences

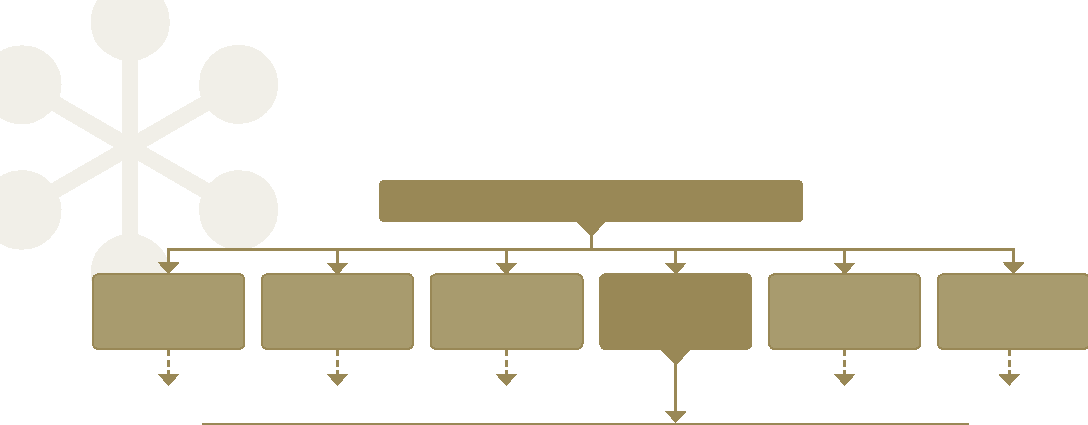

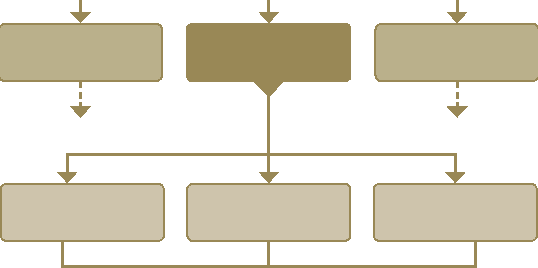

The horizontal dimension of the CEFR shows the different contexts of teaching and learning as described in the descriptive scheme laid out in Chapter 2. This is dealt with in Chapters 4 and 5 of the CEFR with the former covering ‘Language use and the language user/learner’ and the latter covering ‘The user/learner’s competences’. The illustrative scales included in these chapters are designed to help differentiate these language activities and competences across the reference levels. The headings and subheadings in Chapters 4 and 5 present a hierarchical model of elements nested within larger elements.

Figures 4 and 5 on p.10 illustrate this by showing partial views of Chapters 4 and 5 in the CEFR, using the headings and subheadings from these chapters. The level of detail involved in these chapters means that not all headings can be shown, and dotted arrows indicate additional subheadings not illustrated here. For example in Chapter 4 ‘The context of language use’ has subheadings including ‘Domains’ and ‘Situations’.

Each section in Chapters 4 and 5 first explains the concepts involved, and follows this with illustrative scales relevant to that section, containing Can Do statements for each of the levels A1 to C2. For example in Chapter 4 of the CEFR (2001a:57) under Section 4.4, ‘Communicative language activities and strategies’, Section 4.4.3 ‘Interactive activities and strategies’ contains separate scales for ‘Overall spoken interaction’, ‘Understanding a native speaker interlocutor’, ‘Conversation’ and so on.

Productive activities and strategies

The context of language use

Using the CEFR: Principles of Good Practice

Communication themes

Language use and the language user/learner

Communicative tasks and purposes

Communicative

language activities

and strategies

Communicative language processes

Texts

Receptive activities and strategies

Interactive activities

and strategies

Mediating activities and strategies

Written interaction

Spoken interaction

Interaction strategies

Descriptor scales provided for illustration

Non-verbal

communication

Figure 4. A partial view of CEFR Chapter 4: Language use and the language user/learner

10

Descriptor scales provided for illustration

The user/learner’s competences

Linguistic competences

Lexical

Grammatical

Semantic

Phonological

Orthographic

Orthoepic

General competences

Sociolinguistic competences

Linguistic markers of

social relations

Politeness conventions

Expressions of folk wisdom

Register differences

Dialect and accent

Communicative language

Pragmatic competences

Discourse

Functional

competences

Figure 5. A partial view of CEFR Chapter 5: The user/learner’s competences

Section 2: Principles

Principles for teaching and learning

- Council of Europe (2001a) Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. In particular Chapters 5, 6, 7 and 8.

- For information on the European Language Portfolio and on where to find exemplars of speaking and writing performance at different CEFR levels go to: www.coe.int/t/dg4/portfolio/

Principles for assessment

- Council of Europe/ALTE (2011) Manual for Language Test Development and Examining. For use with the CEFR

- Council of Europe (2001a) Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment, Chapter 9.

- Council of Europe (2009a) Relating Language Examinations to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment (CEFR), A Manual.

Principles for development and use of Reference Level Descriptions

- Council of Europe (2005) Guide for the production of RLD.

and general usage

‘We have NOT set out to tell practitioners what to do or how to do it.’

Council of Europe (2001a:xi)

KEY RESOURCES

Using the CEFR: Principles of Good Practice

12

Principles for teaching and learning

The CEFR has become very important in the framing of language policy and the design of curricula and syllabuses. In practice, the CEFR can provide a straightforward tool for enhancing teaching and learning, but many teachers and other language professionals find the document difficult to use without further guidance.

This section is organised around two levels at which language professionals may need to interact with the CEFR and teaching:

- using the CEFR in designing curricula and syllabuses

- using the CEFR in the classroom: teaching and lesson planning.

Embedded within the sections are four principles designed to help you understand the key messages of the CEFR:

- Adapt the CEFR to fit your context.

- Focus on the outcomes of learning.

- Focus on purposeful communication.

- Focus on the development of good language learning skills.

Using the CEFR in curriculum and syllabus design

It is important to remember that the CEFR is a framework of reference and so must be adapted to fit your context. Linking to the CEFR means relating the particular features of your own context of learning (the learners, the learning objectives, etc.) to the CEFR, focusing on those aspects which you can find reflected in the body of the text and in the level descriptors. Not everything in the CEFR will be relevant to your context, and there may be features of your context which are important but are not addressed by the CEFR.

Aims and objectives

A language teaching context has its own specific aims and objectives. These state the distinguishing features of a language context, whereas the CEFR tends to stress what makes language contexts comparable.

Aims are high-level statements that reflect the ideology of the curriculum, e.g:

- We wish our students to grow into aware and responsible citizens.’ At a slightly lower level, aims also show how the curriculum will seek to achieve this, e.g.:

- They will learn to read newspapers, follow radio, TV and internet media critically and with understanding.’

- They will be able to form and exchange viewpoints on political and social issues.’

The CEFR is a rich source of descriptors which can be related to these lower-level aims. This allows users to identify which CEFR levels are necessary to achieve these aims, and by matching this to the level of their students to incorporate them into a syllabus.

Section 2: Principles and general usage

13

Objectives break down a high-level aim into smaller units of learning, providing a basis for organising teaching, and describing learning outcomes in terms of behaviour or performance. There are different kinds of objective. For example, with respect to the aim ‘Students will learn to listen critically to radio and TV’ the following kinds of objective can be defined:

Language objectives:

- learn vocabulary of specific news topic areas

- distinguish fact and opinion in newspaper articles. Language-learning objectives:

- infer meaning of unknown words from context. Non-language objectives:

- confidence, motivation, cultural enrichment.

Process objectives, i.e. with a focus on developing knowledge, attitudes and skills which learners need:

- investigation, reflection, discussion, interpretation, co-operation.

Linking to the CEFR

The link to the CEFR is constructed starting from aims and objectives such as the ones above, which have been specifically developed for the context in question. Finding relevant scales and descriptors in the CEFR, the curriculum designer can then state the language proficiency level at which students are expected to be able to achieve the objectives. CEFR-linked exemplars of performance can then be used to monitor and evaluate the range of levels actually achieved by the students. It also allows teachers to direct students towards internationally recognised language qualifications at an achievable CEFR level.

These objectives can be modified (either upwards or downwards) to accommodate what is practically achievable. This can then be reported in terms that will be readily understood by others in the profession, and which will allow them to compare what is being achieved in one context with what is being achieved in another.

Using the CEFR in the classroom: teaching and lesson planning

Language teaching is most successful when it focuses on the useful outcomes of language learning – for example, on what exam grades mean in terms of specific skills and abilities rather than simply the grades themselves. Linking teaching to the CEFR is a very effective way of achieving this.

A clear proficiency framework provides a context for learning that can help learners to orient themselves and set goals. It is a basis for individualising learning, as for each learner there is an optimal level at which they should be working. It allows teaching to focus on the strengths and weaknesses which are helping or hindering learners. It enables a shared understanding of levels, facilitating the setting of realistic learning targets for a group, and relating outcomes to what learners can do next – successfully perform a particular job, or pursue university studies using the language, and so on.

Using the CEFR: Principles of Good Practice

14

The communicative approach

The CEFR invites readers to be explicit about their own beliefs about the process of learning; which teaching approaches they favour; what they take to be the relative roles and responsibilities of teachers and learners, and so on. These invitations to reflect on methodology show the CEFR as an open, flexible tool.

However, there are some broad teaching and learning principles underlying the CEFR approach. The text of the CEFR emphasises learners’ ‘communicative needs’, including dealing with the business of everyday life, exchanging information and ideas, and achieving wider and deeper intercultural understanding. This is to be achieved by ‘basing language teaching and learning on the needs, motivations, characteristics and resources of learners.’ (2001a:3)

This conveys the CEFR’s communicative, action-oriented approach. This approach is broad and should be coherent with the aims of most school language learning. It is based on the model of language use and language learning presented in Chapter 2 of the CEFR.

In this model the two key notions are tasks and interaction. Language use is seen as purposeful, involving communication of meanings which are important to learners, in order to achieve goals. The principle underlying this is that learning will be more effective where language is used purposefully. Chapter 7 of the CEFR is entirely devoted to task-based learning. To take the example given above: given the high-level aim of teaching students to read newspapers and discuss topical events, a range of tasks can be envisaged that would involve students in reading, discussing, explaining or comparing newspaper stories; in selecting, adapting or writing material for a classroom newspaper. Tasks such as these also give scope for working individually and in collaborative groups; for positively criticising each other’s work, and so on.

The CEFR scales describe levels in terms of what students can do and how well they can do it. Focusing on tasks and interaction enables teachers to understand students’ performance level as that level where they can tackle reasonably successfully tasks at a level of challenge appropriate to their ability. This is not the same as demonstrating perfect mastery of some element of language; a student can perform a task successfully but still make mistakes.

The importance of purposeful communication as an aspect of classroom language use does not mean, of course, that a focus on language form is not also necessary. Reference Level Descriptions can give very useful guidance on the linguistic features which students may master well at a particular CEFR level, and those where they will demonstrate partial competence, continuing to make mistakes. This helps the teacher to judge what are realistic expectations at each level. Exemplars of speaking or writing performance at different CEFR levels are very useful in this respect. A link to the Council of Europe website where such exemplars can be found is given on p.11.

A plurilingual approach

Another key aspect of the CEFR’s approach is the belief in plurilingualism. This is the understanding that a language is not learned in isolation from other languages. Studying a foreign language inevitably involves comparisons with a first language. Each new language that a learner encounters contributes to the development of a general language proficiency, weaving together all the learner’s previous experiences of language learning. It becomes easier and easier to pick up at least a partial competence in new languages.

This view of language learning is reflected in the European Language Portfolio (ELP), an initiative developed in parallel with the CEFR. The Portfolios are documents, paper-based or online, developed by many countries or organisations according to a general structure defined by the Council of Europe. They have been designed for young learners, school children and adults.

Section 2: Principles and general usage

15

The Portfolios provide a structured way of encouraging learners to reflect on their language learning, set targets, record progress and document their skills. They are an effective aid to developing independence and a capacity for self-directed learning, and so are useful in language study. Whether or not teachers choose to adopt the formal structure of the Portfolio, they should think about how to encourage learners to develop the skills and attitudes to language learning which the ELP promotes. This includes empowering them to evaluate their own or their fellow students’ work. These are valuable learning skills, most readily fostered in a classroom where the learning pathway, including the ground to be covered and the learner’s current point on the pathway, is clearly laid out.

Using the CEFR: Principles of Good Practice

16

Principles for assessment

Anyone who has tried to decide on the most appropriate language test for their students will be aware that most test providers now claim links to the CEFR. However, users need to make sure that they understand what these claims are based on.

This section is organised around the two levels at which language professionals interact with the CEFR and assessment:

- using the CEFR to choose or commission appropriate tests

- using the CEFR in the development of tests.

The first of these sections is aimed primarily at test users and the second at test developers.

The term ‘test user’ covers a wide range of groups and individuals from teachers and admissions officers at colleges to policy makers in government. Some of these test users need to choose the most appropriate tests for their learners from those already available. Others may be in a position to commission appropriate tests for their specific purposes. Test developers are organisations, teams or individuals, who create tests.

All test users and test developers share the need to understand what the results of tests mean for a particular purpose. Therefore, whilst the following principles are aimed primarily at test developers, test users also require an understanding of them;

- Adapt the CEFR to fit your context.

- Build good practice into your routine.

- Maintain standards over time.

Using the CEFR to choose or commission appropriate assessments

The value of a test result always depends on the quality of the test. The better the general quality of the test, the more interpretable the test result in relation to the CEFR.

Test users should ask for evidence of the claims made for the results of a test, including those related to its alignment to the CEFR. In this respect, test users should see themselves as customers and follow the advice of Weir (Taylor 2004b):

When we are buying a new car or a new house we have a whole list of questions we want to ask of the person selling it. Any failure to answer a question or an incomplete answer will leave doubts in our minds about buying. Poor performance in relation to one of these questions puts doubts in our minds about buying the house or car.

Quality may equate to the precision with which a test result describes a learner’s ability. So-called ‘low-stakes’ tests, where results are expected to be used for less important purposes, may not need the same level of precision as tests which have a direct effect on candidates’ education, employment or migration, but, in cases of very poor-quality tests, it is often very difficult to know what abilities have actually been tested and therefore, what the test result actually represents. Tests like these cannot be linked to the CEFR in any meaningful way.

- Were experts used in the test construction process?

Questions test users can ask about the test:

General:

- Is the test purpose and context clearly stated?

- Are the test tasks appropriate for the target candidates?

Section 2: Principles and general usage

17

- Have test items and tasks been through a comprehensive trialling and editing process?

- Is the test administered so that other factors, such as background noise, do not interfere with measuring candidate ability?

- Is test construction and administration done in the same way every time?

- How are candidate responses used to determine test results? (raw score, weighted, ability estimated, etc.)

- If the results are grades, how are they set?

- Is there guidance on how the results should be interpreted? If so, is it adequate?

- How does the test provider ensure all the procedures they have developed for test provision are properly followed throughout the entire process of test provision?

- What impact is the test expected to have on candidates, the education system and the wider society?

CEFR-specific:

- Does the test provider adequately explain how CEFR-related results may be used?

- Is there appropriate evidence to support these recommendations?

- Can the test provider show that they have built CEFR-related good practice into their routine?

- Can the test provider show that they maintain CEFR-related standards appropriately?

Using the CEFR in the development of assessments

The CEFR was designed to be applicable to many contexts, and it does not contain information specific to any single context. However,in order to use the CEFR in a meaningful way, developers must elaborate the contents of the CEFR. This may include, for example, establishing which vocabulary and structures occur at a particular proficiency level in a given language, writing and validating further Can Do statements for a specific purpose or developing a set of Reference Level Descriptions (see p.23).

Defining the context and purpose of the test

The first step for test developers in adapting the CEFR to their needs is to clearly define the context(s) and specify the purpose(s) of the test. The examples in Figure 6 on p.18 show that there is a very wide range of contexts and purposes for assessments. Some cover small, probably homogeneous, groups (e.g. 2), other groups are large and diverse (e.g. 4). Likewise, the purpose of an assessment can be very specific (e.g. 3), or quite general and applicable to many contexts of use (e.g. 4). If the context and purpose of the test is decided by someone else, such as a government agency, you must help them to specify the context and purpose as clearly as possible so that the task of developing the test can be completed successfully.

Using the CEFR: Principles of Good Practice

| general context | details of context | purpose |

education, university undergraduate applicants to English language entrance exam to

an English-medium university’s determine which university applicants

humanities, sciences and social have sufficient English language ability

sciences courses to follow their chosen course

1

2

3

4

| education, school school students in a particular class mid-course classroom assessment

to diagnose areas of language ability which need further work before the national school leaving exam |

| migration migrants who have lived in country Z placement exam to determine which

for less than one year course migrants should join to improve their language ability in a range of defined social contexts |

| work candidates from anywhere in the to determine the ability level of

world candidates who want to use English in business situations |

Figure 6. Examples of contexts and purposes for assessment

18

Once the context and purpose are established, it is possible to delineate the target language use (TLU) situations. For example, for the university applicants, several TLUs can be imagined: attending lectures, participating in seminars, giving presentations, reading books and papers, writing reports and essays; and each TLU may suggest a different combination of skills and language exponents. Furthermore, demands may vary on different courses: those such as law may require higher levels of ability in literacy-related areas than others, such as engineering.

The CEFR can help in defining TLUs with its descriptive scheme. It divides language use into four separate, wide-ranging domains (2001a:45):

- personal

- public

- occupational

- educational.

Situations occurring within one or more of these domains can be described by variables such as the people involved, the things they do in the situation, and objects and texts found in the situation (2001a:46). Depending on the TLU situations considered most important, the examples of contexts and purposes in Figure 6 may relate to these domains like this:

- university – educational

- school – personal, public and educational

- migration – personal, public, educational and possibly occupational

- work – occupational.

Table 5 of the CEFR provides examples for each category within each domain. Further schemes of classification are provided to describe a number of characteristics in Chapter 4, such as the relative (mental) contexts of learners and interlocutors (2001a:51), communicative themes (2001a:51–3), tasks and purposes (2001a:53–6), language activities and strategies (2001a:57–90).

Section 2: Principles and general usage

19

These categories are illustrated with Can Do descriptors arranged on scales corresponding to ability level. The descriptive scheme will help, therefore, not only in describing the TLU situation but also in determining the minimal acceptable level for your context. Users need to be aware, however, that although the descriptive scheme is illustrated, the CEFR does not contain an exhaustive catalogue of all possible TLU situations, or descriptions of minimal acceptable ability levels. Assessment developers will need to determine what is required for your situation based on the guidance set out within the CEFR.

The CEFR considers some types of potential candidates, but other groups – notably young learners – are not very well covered in the descriptive scales, as they were developed with adults in mind and do not take into account the cognitive stages before adulthood. If your target group of candidates consists of young learners, you may need to construct your own series of scales along the lines of those to be found in the CEFR.

The CEFR is accompanied by a growing ‘toolkit’ which is designed to help users exploit the CEFR. The Manual for Language Test Development and Examining. For use with the CEFR (Council of Europe/ ALTE 2011) provides further guidance on this. Reference Level Descriptions are available in several languages (see Appendix A), and validated Can Do statements are available from organisations like the Association of Language Testers in Europe (ALTE).

Linking tests to the CEFR

At this point in the process of developing the test, substantial work towards establishing a link to the CEFR will already have been done. However, the test provider often needs to show more evidence about how a test is linked to the CEFR and to argue convincingly for the interpretations that they recommend for the test results based on the CEFR levels. This leaves the test provider in the position of designing a research and evidence gathering programme to meet these needs. For this reason, the Council of Europe published Relating Language Examinations to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment (CEFR), A Manual (Council of Europe 2009a), which contains a range of procedures to help test providers begin to build their argument. This Manual suggests a programme with five main elements:

- familiarisation

- specification

- standardisation training and benchmarking

- standard setting procedures

- validation.

The programme of linking suggested by this Manual, and the procedures it contains are by no means the only way such work can be done, and they are not necessarily appropriate in every context. It is important for test providers to reflect carefully on whatever work they undertake, as it is their responsibility to show that this work supports the interpretations of test results that they recommend to test users. The applicability of the procedures in the Manual will differ according to context and aims. It is also important to note that linking work should not be seen as a one-off project that never needs to be revisited; it must be included in the ongoing development and management of the test. This is elaborated in North and Jones (2009) and in the following sections of the current document.

Test production

Tests may be used more than once, or made in several different versions for security reasons. It is important to maintain the links to the CEFR throughout each cycle of test development, construction and use. The best way to do this is to make sure the experts involved in these tasks know the CEFR

Using the CEFR: Principles of Good Practice

20

well and are able to use it in work like vetting items for content, language focus and difficulty level. Ways must be found to maintain this knowledge, so that, over time, their work relates the test to the CEFR in the same way.

Detailed specifications help ensure that each test version will be comparable with the others. For training purposes, or for standardising judgements of experts involved, the CEFR toolkit offers several illustrative samples of items, tasks and candidate performance at each of the common reference levels. Such expert knowledge is needed at several stages throughout test construction:

- items or tasks should be examined by experts to see if they meet the criteria in the specification

- items or tasks should be edited by experts to ensure that any necessary changes are made

- the test should be constructed so that it meets its target parameters as a whole.

Statistics can be used in support of expert judgement to determine item characteristics using empirical data. This allows the experts to combine their own judgement with other evidence. For test items and tasks, for example, the data can come from the responses candidates give in live test situations, or in pretests (specially organised test sessions with the purpose of obtaining response data). Estimated item difficulty can help experts to see whether an item is really measuring at the ability level they expect (Council of Europe/ALTE 2011).

Assessment standards

Making sure that test results always indicate the appropriate CEFR ability level requires a process for maintaining these standards over time. This means employing techniques, such as constructing tests using known characteristics and linking tests to each other, standardising markers and monitoring their work. It should also be noted that many steps already outlined in this section will help greatly in maintaining the standards of the test over time. For example, a well-designed process of editing items which is applied to each test form in the same way will help to ensure comparability across forms. North and Jones (2009) describe maintaining standards in relation to the CEFR.

- constructing tests with known characteristics

When a statistical difficulty value is calculated for a test item, a further procedure, called calibration, can make the difficulty value comparable with the difficulty values of items from previous tests. This procedure requires that either some items are shared between the tests, or that some candidates sit both tests. Calibration makes it far easier to construct a new version of the same test at a comparable level of difficulty.

- linking tests to each other

Tests can be linked to each other, so that the same standard is applied each time a test is used. Linking is used here as a technical term and often involves complex statistical processes. However, the outcome is that scores or grade boundaries are converted on one test so that they are comparable with those on another.

- standardising rater performance and monitoring

To standardise the performance of raters, a number of key supports can be provided:

– A clear and comprehensive but concise rating scale – these may be based on the Can Do scales

found in the CEFR but should be more detailed and specific to your test to limit ambiguity. There should not be too many categories, or the scale becomes difficult to internalise.

– Standardisation training – raters are given pre-rated materials and asked to rate them. Any discrepancies are discussed leading to a clearer understanding of how to apply the rating scale. Alternatively, where raters are equally expert, discussions on discrepancies should lead to a single, shared interpretation of application of the rating scale.

– Monitoring – raters are monitored by experts so that any departures from the intended standard

are detected and corrected in the rating of live tests. This may be done by sampling in large-scale operations, or by peer rating and discussion in situations where raters are equally expert.

Section 2: Principles and general usage

21

Principles for development and use of Reference Level Descriptions

Since its publication in 2001, the Council of Europe has encouraged the development of CEFR Reference Level Descriptions for national and regional languages.

These have been developed for various languages to date (see Appendix A). The main purpose of Reference Level Descriptions is:

[f]or a given language, to describe or transpose the Framework descriptors that characterise the competences of users/learners (at a given level) in terms of linguistic material specific to that language and considered necessary for the implementation of those competences. This specification will always be an interpretation on the CEFR descriptors, combined with the corresponding linguistic material (making it possible to effect acts of discourse, general notions, specific notions, etc.).

(Council of Europe 2005:4)

This section is organised around the two levels at which language professionals interact with the Reference Level Descriptions:

- using resources from the Reference Level Descriptions in learning, teaching and assessment

- using the CEFR to develop Reference Level Descriptions.

The first of these sections is aimed at teams working on the development of Reference Level Descriptions, either for a language where one has not been attempted before or where an existing Reference Level Description can be updated, improved or extended. The second section is aimed at teachers and other language professionals interested in how they can make use of already published Reference Level Descriptions. For an example showing how the CEFR is being expanded and described for English, see p.31 in Section 3.

Some key principles for working with Reference Level Descriptions are:

- Use available Reference Level Descriptions as a reference tool.

- When developing Reference Level Descriptions follow a systematic approach based on empirical data.

Using resources from Reference Level Descriptions in learning, teaching and assessment

When using resources from Reference Level Descriptions, there are two principles to keep in mind:

- Reference Level Descriptions are reference tools for teachers, language testers and other language learning professionals to support curriculum design and item writing. Reference Level Descriptions should not be viewed or used as a replacement for a teaching or testing method; for a course curriculum or test specifications.

- Reference Level Descriptions can be used in different ways according to the learning situation and requirements. It is up to the Reference Level Description user to decide which points to include in a particular course, syllabus or test depending on a range of factors, like:

– the level and range of levels of learners on the programme – the age and educational background of the learners

– other sources of input and opportunities to practise English (UCLES/Cambridge University Press 2011).

Using the CEFR: Principles of Good Practice

– their reasons for learning English

– their areas of interest

– their first language

– their experience of learning English so far

22

Reference Level Description resources facilitate decisions about what language to include for teaching and testing at each CEFR level.

There are many ways in which language professionals such as teachers, curriculum planners and materials or test writers can use resources from Reference Level Descriptions to enable them to make decisions about which language points are suitable for teaching, learning and assessing at each CEFR level.

Some areas which can benefit from Reference Level Descriptions are listed below, with exemplification of how different groups of language professionals might use resources from Reference Level Descriptions within these areas (adapted from UCLES/Cambridge University Press 2011).

A. Deciding whether particular language points are relevant for a specific purpose, learner group and CEFR level

- A teacher checking whether some key vocabulary for a lesson is suitable for their class.

- A test developer checking whether a particular grammatical point is suitable for an A2 test.

- An author checking what aspects of a grammatical area (e.g. past tense) are suitable for a B1 course.

B. Identifying suitable language points for a specific purpose, learner group and CEFR level

- A curriculum planner is drawing up the vocabulary list for an A1 course.

- An author wants to identify language points that are particularly difficult for a particular group of learners at B1 level (e.g. Spanish learners of English).

- A test developer has to decide which structures to include in the assessment syllabus for a C1 exam.

- A teacher is looking for a range of examples of ‘refusing a request’ suitable for B2 learners.

C. Obtaining authentic learner language to illustrate language points at a specific CEFR level

- A teacher is putting together an exercise on a particular language point, using examples produced by learners at the same level as their class.

- A test writer is looking for a suitable sentence for a particular test item.

- A curriculum planner wants to add to the syllabus examples of particular structures that are suitable for the level.

- An author is writing a unit on health at B1 level and wants a list of suitable words and phrases to include.

- A teacher is looking for examples of ‘asking for permission’ in a formal work context suitable for a B2 class.

D. Gaining a deeper understanding of language points within and across CEFR levels

- An author wants to know how an understanding of a language feature (e.g. countable/ uncountable nouns in English) progresses from A1 to B1 CEFR levels to work out what should be included in an A1 or B1 level course.

a counter-example’ in both formal and informal contexts.

a counter-example’ in both formal and informal contexts.

Section 2: Principles and general usage

- A teacher wants to see how the different meanings of a polysemous word (e.g. keep) are normally acquired across the CEFR levels. Which meanings should students learn first?

- A test writer needs to know what lexical items combine with a specific structure to be tested at B2 level (e.g. what verbs are most suitable for a test item on the passive voice in English).

- A curriculum planner wants to make sure the C2 curriculum covers the language of ‘presenting

23

You can find a list of Reference Level Description resources per language as well as a link to sample performances and tasks illustrating the CEFR levels in a number of languages in Appendix A.

Using the CEFR to develop Reference Level Descriptions

Since the six-level scale was developed (A1 to C2), the Council of Europe’s Language Policy Division has produced a guide to assist with the development of Reference Level Descriptions (Council of Europe 2005), which outlines some general principles, including:

- each Reference Level Description or set of Reference Level Descriptions for a given language implements solutions and makes choices adapted to the language concerned.

- each Reference Level Description for each language should refer to a level of the Framework and its descriptors, and provide inventories of the linguistic material necessary to implement the competences thus defined and explain the choice of forms.

Taking the Council of Europe’s guidelines into account but also going beyond them, a number of steps for developing CEFR Reference Level Descriptions for individual languages are outlined here:

- Familiarise yourself with the CEFR (Council of Europe 2001a) and the CEFR descriptors you will be exemplifying (e.g. Written Production vs. Written Interaction). For a range of CEFR familiarisation activities see, for example, the Manual for Relating language examinations to the CEFR (Council of Europe 2009a).

- Employ an interdisciplinary research approach, that is, get expertise from a range of language fields (e.g. theoretical and applied linguistics, second language acquisition/learning, pedagogy, etc.), to best address and capture the complexity of language learning and learner performances reflected in the Reference Level Descriptions.

- Follow an empirical approach – in addition to using expert judgement, base your Reference Level Descriptions on learner data that is aligned to and exemplifies the CEFR levels – for example, learner corpora. For methods of linking empirical data, e.g. exam data, to the CEFR see, for example, the Manual for Relating language examinations to the CEFR (Council of Europe 2009a).

- Reference Level Descriptions should be descriptive – they should describe what learners know and can do at each CEFR level. They should not be prescriptive, designed to be an exhaustive list of materials to be taught or assessed per CEFR level.

- Provide sample learner performances for Speaking and Writing to illustrate the Reference Level Descriptions for the productive skills. Provide sample Reading and Listening tasks to illustrate the Reference Level Descriptions for the receptive skills.

- Engage the language learning, teaching and testing community during the development of the Reference Level Descriptions. This can be done, for example, by creating a project network which involves potential users of Reference Level Descriptions, by organising workshops and seminars, and by inviting feedback on your project. Reference Level Descriptions should both inform and be informed by the needs of the community of its users.

- Provide relevant literature (e.g. lists, research papers, reports) that detail the Reference Level Descriptions and the research behind them.

Using the CEFR: Principles of Good Practice

24

Developing Reference Level Descriptions is usually a long-term endeavour involving a wide range of resources and expertise. However, different scales of such a project can be attempted depending on the resources and expertise available. One may decide to focus, for example, on a particular CEFR level (e.g. B2); or skill (e.g. Written production); on a group of learners from a specific linguistic background (e.g. French learners of English); on a particular age group (e.g. teenage learners) and so on. One may therefore develop Reference Level Descriptions tailored to one’s particular context and needs – e.g. Reference Level Descriptions that illustrate/describe the Written production skills of French high school (teenage) learners of English at B2. Developing Reference Level Descriptions for a very specific learner group or learning situation is appropriate as long as this specific scope of the Reference Level Descriptions is made clear when they are published.

Despite the scale of the project for developing Reference Level Descriptions:

… [i]t should be remembered that producing descriptions of the CEFR reference levels, language by language and level by level, is not an end in itself. The purpose of the descriptions is to bring transparency to the aims pursued in teaching and certification, as this guarantees fairness and comparability in language teaching…. These descriptions are designed essentially, after and like the Framework, to help build a variety of teaching programmes that contribute to (the) plurilingual education… , which is a condition and a practical form of democratic citizenship.

(Council of Europe 2005:7)

Section 3: Applying the

www.research.cambridgeesol.org

for a complete archive of Research Notes.

Cambridge ESOL (2011) Principles of Good Practice: Quality management and validation in language assessment.

Martyniuk, W (ed.) (2010) Aligning Tests with the CEFR. Reflections on using the Council of Europe’s draft Manual.

KEY RESOURCES

CEFR in practice

‘There is a difference between having a very good idea of what the relationship is and confirming it. Cambridge ESOL is an exception, because there is a relationship between the levels in the CEF[R] and the levels of the Cambridge ESOL exams.’

North (2006)

Using the CEFR: Principles of Good Practice

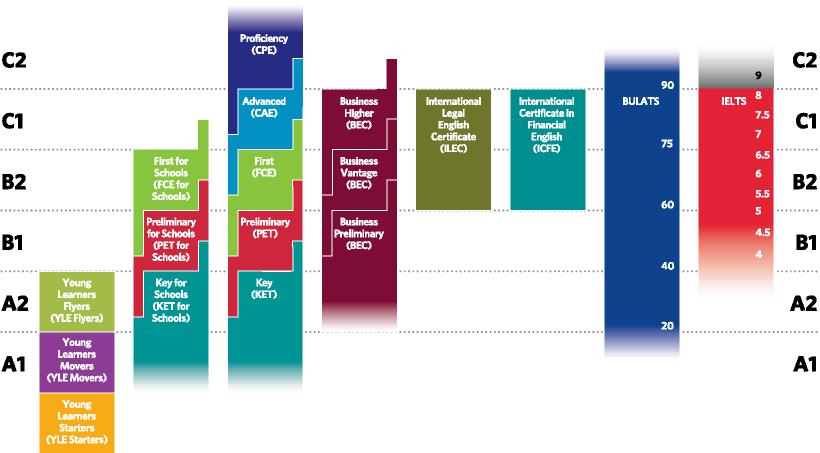

Applying the CEFR in practice: Aligning Cambridge ESOL examinations to the CEFR

Ever since the first Cambridge English exam was introduced in 1913, our approach has always been to develop tests that meet specific needs, and the CEFR plays a key role in this process.

Since then, Cambridge ESOL has continually extended the range to include exams at a wide variety of levels and for purposes as diverse as higher education and migration; business, legal and financial communication; and motivating and rewarding young learners.

These are complemented by a range of qualifications for teachers, and by a very wide spectrum of supporting services, all designed to support effective learning and use of English. Most of our exams can be taken either as paper-based or computer-based versions.

Figure 7. A range of exams to meet different needs

26

Section 3: Applying the CEFR in practice

27

Point 1 – Shared origins and long-term engagement

The Cambridge examinations informed the development of the CEFR and have been informed by it. Cambridge ESOL has been continuously involved in the development and implementation of the CEFR since its earliest stages in the 1980s. Since then, in an ongoing engagement over more than 20 years, the links have been strengthened through a process of convergence, supported by ongoing research and close collaboration between Cambridge ESOL and the Council of Europe.

Point 2 – Integrated item banking and calibration systems

Well-established calibration systems are used to establish comparisons between the levels of the Cambridge English exams and to maintain an alignment to external benchmarks such as the CEFR. This system is built into routine procedures for every examination session, rather than just applying a one-off snapshot of a single session. Data from millions of candidates over more than 20 years is used to validate this alignment.

Point 3 – Quality management and validation

Quality management systems certified to ISO standard 9001:2008 are used at every stage in the development, marking, grading and evaluation of all Cambridge English examinations. These processes use data from ‘live’ examinations conducted throughout the world and involve constant cross-referencing to the CEFR. Cambridge ESOL’s publication Principles of Good Practice: Quality management and validation in language assessment (2011) sets this out in a clear and accessible way for stakeholders.

Point 4 – Alignment and standard-setting studies

Since 2001 alignment exercises and standard-setting studies have been carried out in line with the recommendations made in the extensive supporting documentation produced by the Council of Europe. These studies have led to international symposia hosted by Cambridge ESOL and ALTE, case study conferences and reports and publications, and presentation of academic papers at international conferences.

Point 5 – Application and extension of the CEFR for English

Cambridge ESOL continues to work closely with the CEFR and to adapt and extend it in useful ways, particularly in its specific application to English. This has included producing the exemplar materials for use with the CEFR, carrying out international benchmarking exercises with ALTE (e.g. for speaking), supporting the development of the Council of Europe Manuals and user guides, and leading work on the production of Reference Level Descriptions for English (the English Profile Programme).

These five key points are explained in more detail in the following section.

Using the CEFR: Principles of Good Practice

Point 1 – Shared origins and long-term engagement

The CEFR originates in well-established levels and its conceptual framework has a long-standing basis in classroom practices dating back to the 1970s. In fact, the Cambridge English exams played an important part in the early development of the CEFR – as noted by Brian North, one of the co-authors of the CEFR.

‘… the process of defining these [CEFR] levels started in 1913 with the Cambridge Proficiency Exam (CPE) that defines a practical mastery of the language as a non-native speaker. This level has become C2. In 1939, Cambridge introduced the First Certificate (FCE), which is still seen as the first level of proficiency of interest for office work, now associated with B2.’

(North:2006)

- Cambridge Proficiency Exam (CPE) launched – a test which played a large role in the development of level C2 of the CEFR .

1913

1939

1980–1990

1990–2001

- Lower Certificate (now Cambridge English: First or FCE) launched – a test set at the level now associated with Level B2 of the CEFR.

- Cambridge, along with British Council, BBC English and others provides support for revising Threshold and Waystage resulting in the revised PET exam (B1 level) and a new KET exam (A2) in the early 1990s.

|

Figure 8. The historical context – Cambridge ESOL and the CEFR

28

The convergence between the Cambridge General English examinations and the six reference levels of the CEFR continued during the 1990s. The KET (A2) and PET (B1) exams were directly based on the Waystage and Threshold specifications, and the introduction of CAE (C1) was designed to complete five levels of the proficiency framework which now make up the CEFR. The introduction of the Cambridge Young Learners English Tests (YLE) in 1997 filled in the A1 level.

At the same time, the work of Cambridge ESOL and its partners in the Association of Language Testers in Europe (ALTE) in the 1990s played a big part in the development of the CEFR.

During the 1990s, the ALTE members engaged in the development of the five-level ALTE Framework – a project to establish common levels of proficiency which sat alongside the CEFR. Cambridge ESOL and the ALTE members conducted several studies to explore and verify the alignment of the ALTE Framework and the CEFR levels. The ALTE Can Do Project (1998–2000) for example was an important empirical approach used by Cambridge ESOL for alignment to the CEFR, and contributed to the adoption by the ALTE partners of the six CEFR levels (A1–C2).

Section 3: Applying the CEFR in practice

29

The ALTE Framework and Can Do projects were instrumental in confirming what learners can typically do at these levels. They analysed the content and proficiency level of the tests as part of the process of aligning them to the levels of the ALTE Framework and later the levels of the CEFR. Examples of typical general language ability plus ability in each of the skills areas and in a range of contexts were found to be consistent with the CEFR level statements.

Point 2 – Integrated item banking and calibration systems

In 1990 Cambridge ESOL was the first UK-based examinations board to introduce an item banking approach to calibrating its examinations using Rasch modelling. This is an approach to test production which ensures that all materials can be consistently related to the same scale by using statistical techniques.

As a result, data from over 15 million test takers has been analysed over the last two decades. This model of calibration helps ensure that the proficiency levels reported in the Cambridge examinations have remained stable over time.

Other notable research projects include the Common Scale for Writing project and a series of volumes in the series Studies in Language Testing which look in detail at the assessment of language skills in relation to the CEFR.

Point 3 – Quality management and validation systems

In addition to the CEFR itself, the Council of Europe has provided guidance for educationalists, examination providers, policy-makers and administrators in the form of recommendations and user guides. See for example Recommendation CM/Rec(2008)7 of the Committee of Ministers together with its Explanatory Notes and the CEFR ’toolkit’ which includes manuals and supporting resources.

Along with partners in ALTE, Cambridge ESOL has contributed to this toolkit, including the two manuals – the Manual for Relating Language Examinations to the CEFR (Council of Europe 2009a) and the Manual for Language Test Development and Examining (Council of Europe/ALTE 2011) – and their supporting materials.

The latter focuses on designing and maintaining tests under operational conditions and provides explicit guidance in this area. Alignment of a test to the CEFR is not meaningful unless the test provider can demonstrate that it has systems in place to ensure that the proficiency standards it sets are consistent over time.

This is emphasised in the Explanatory Notes of the Council of Europe’s Recommendation CM/ Rec (2008)7 of the Committee of Ministers which clearly states that when making cases for alignment, examination providers need to account for ‘the quality of their assessment procedures and qualification with reference to the principles of good practice which exist in the field of language assessment in general and as set out in internationally recognised Codes of Practice’.

ALTE has also developed its own Code of Practice and Quality Management System which provide the basis for auditing language examinations in relation to professional standards. Seventeen essential parameters have to be accounted for within the quality profile for each examination and audited as set out in the Procedures for Auditing. It should be noted that only one of these parameters deals directly with alignment to a framework such as the CEFR.

Cambridge ESOL’s approach to developing and administering exams is based on a set of formalised processes which are certified to the ISO 9001:2008 standard for quality management, and audited on an annual basis by the British Standards Institution (BSI).

Using the CEFR: Principles of Good Practice

30

Cambridge ESOL draws on the experience of specialist staff in its Assessment, Research and Validation teams who are fully trained at post-graduate and doctoral levels. The staff work across the full range of Cambridge English exams and are extensively involved in research and publication on assessment issues, including alignment to the CEFR, both through Cambridge ESOL’s own extensive programmes and in refereed academic journals – see Appendix B – References.

In 2011, Cambridge ESOL published Principles of Good Practice: Quality management and validation in language assessment, which sets out the quality management approaches to language testing which underpin its alignment argument.

Point 4 – Alignment and standard-setting studies

Cambridge ESOL makes extensive use of the Council of Europe’s Manual for Relating language examinations to the CEFR (2009a) and has been instrumental in supplying supporting materials and in conducting case studies to apply the Manual, including a major contribution over the last seven years to the work of ALTE’s special interest group in this area.

The book Aligning Tests with the CEFR: Reflections on using the Council of Europe’s draft Manual (Volume 33 in the series Studies in Language Testing) describes a substantial number of case studies based on a symposium hosted in Cambridge on behalf of the Council of Europe. These studies show that the Manual can be used to help align different kinds of examinations to the Framework in a variety of useful and informative ways. They also make it clear that the procedures for alignment are not straightforward and need to be reviewed periodically, as examination systems and the CEFR itself continue to evolve over time.

Where appropriate, the recommendations made in the Manual have been implemented within Cambridge ESOL’s routine operational processes. Relevant changes have been documented and made available to stakeholders as part of the revision procedures for the examinations in question (KET, PET, FCE, CAE). These explanations provide additional evidence for the alignment of the examinations to the CEFR.

Standard-setting studies also play a role in these wider processes of alignment. An example of this is the case of the International English Language Testing System (IELTS). IELTS pre-dates the CEFR and uses a nine-band scale which does not neatly align to the six broad bands of the Framework. A provisional alignment was made to the CEFR in 2001 based on comparisons between IELTS and other Cambridge examinations. These comparisons employed content-based comparisons and calibration studies using Rasch analysis (noted above). It is important to note that by implementing standard procedures (noted in Points 2 and 3) to produce the Cambridge General English examinations and IELTS, the relationship between the two was clearly established in the 1990s; they use the same item banking approach for example. This means that the General English examinations provide a strong indirect link between IELTS and the CEFR. Since 2001 several studies have been carried out to investigate whether this alignment needs to be modified in light of new evidence.

In 2009, an independent consultancy company, Alpine Testing Solutions (Dr Chad W Buckendahl), led a standard-setting study aligning IELTS bands to the CEFR levels. In addition, Cambridge ESOL benchmarked IELTS to Cambridge English: Advanced (CAE at C1 level) in a study which saw a group of candidates take both examinations in a balanced research design. This indirect linkage via ‘equation’ to an existing test already linked to the CEFR is one of the recommended approaches in the Council of Europe’s Manual.

As a result of these recent studies a revised alignment with minor changes was issued by the IELTS partnership (see www.ielts.org). This approach to realignment is in line with good practice as set out in the Manual for Relating language examinations to the CEFR.

Section 3: Applying the CEFR in practice

31

Point 5 – Application and extension of the CEFR for English

Users of the CEFR are recommended to adapt it as necessary to meet their specific needs, and to develop it further for a variety of different purposes and contexts. An obvious way in which the CEFR needs to be adapted and developed is when it is used with specific languages (the CEFR itself being neutral and deliberately underspecified in this respect).

To ensure that the Framework is used appropriately and can be adapted to local contexts and purposes, the Council of Europe has encouraged the production of Reference Level Descriptions for national and regional languages.

Reference Level Descriptions represent a new generation of descriptions which identify the specific forms of any given language (words, grammar, etc.) at each of the six reference levels which can be set as objectives for learning or used to establish whether a user has attained the level of proficiency in question.

The English Profile Programme, co-ordinated by Cambridge ESOL since 2005, is an interdisciplinary programme which sets out to develop Reference Level Descriptions for English to accompany the CEFR. The intended output is a ‘profile’ of the English language levels of learners in terms of the six proficiency bands of the CEFR – A1 to C2.

The founder members of English Profile include several departments of the University of Cambridge (Cambridge ESOL, Cambridge University Press, the Computer Laboratory and the Research Centre for English and Applied Linguistics), together with representatives from the British Council, English UK, and the University of Bedfordshire (Centre for Research in English Language Learning and Assessment – CRELLA).

English Profile was formally established as an officially recognised Reference Level Descriptions project for the English language in 2006. After the first three years, the project was extended with a growing network of collaborators around the world and the long-term English Profile Programme was established, partly funded by a European Union grant.

The Cambridge Learner Corpus (CLC), an extensive resource of learner data, has been used to support the work of the English Profile research teams in Cambridge. It consists of learners’ written English from the Cambridge ESOL examinations covering the ability range from A2 to C2, together with meta-data (gender, age, first language) and evidence of overall proficiency based on marks in the other components (typically reading, listening and speaking). Innovative error coding and parsing of the corpus have extended the kinds of analysis which can be carried out and have allowed the research teams to investigate a wider range of English language features at each reference level.

Outcomes from English Profile have been published in 2011 and at the time of writing, two major publications are in press in the Cambridge English Profile Studies series (UCLES/Cambridge University Press).

Summary

Cambridge ESOL integrates the CEFR into relevant aspects of its work and takes a multi-dimensional, long-term approach to ensure that comparisons between the CEFR and the levels of its exams are reliable and meaningfully explained to users.